10 major differences between Protestant and Catholic Bibles

The difference between a Protestant and a Catholic Bible is not just what was included or excluded, but who was trusted to make that decision.

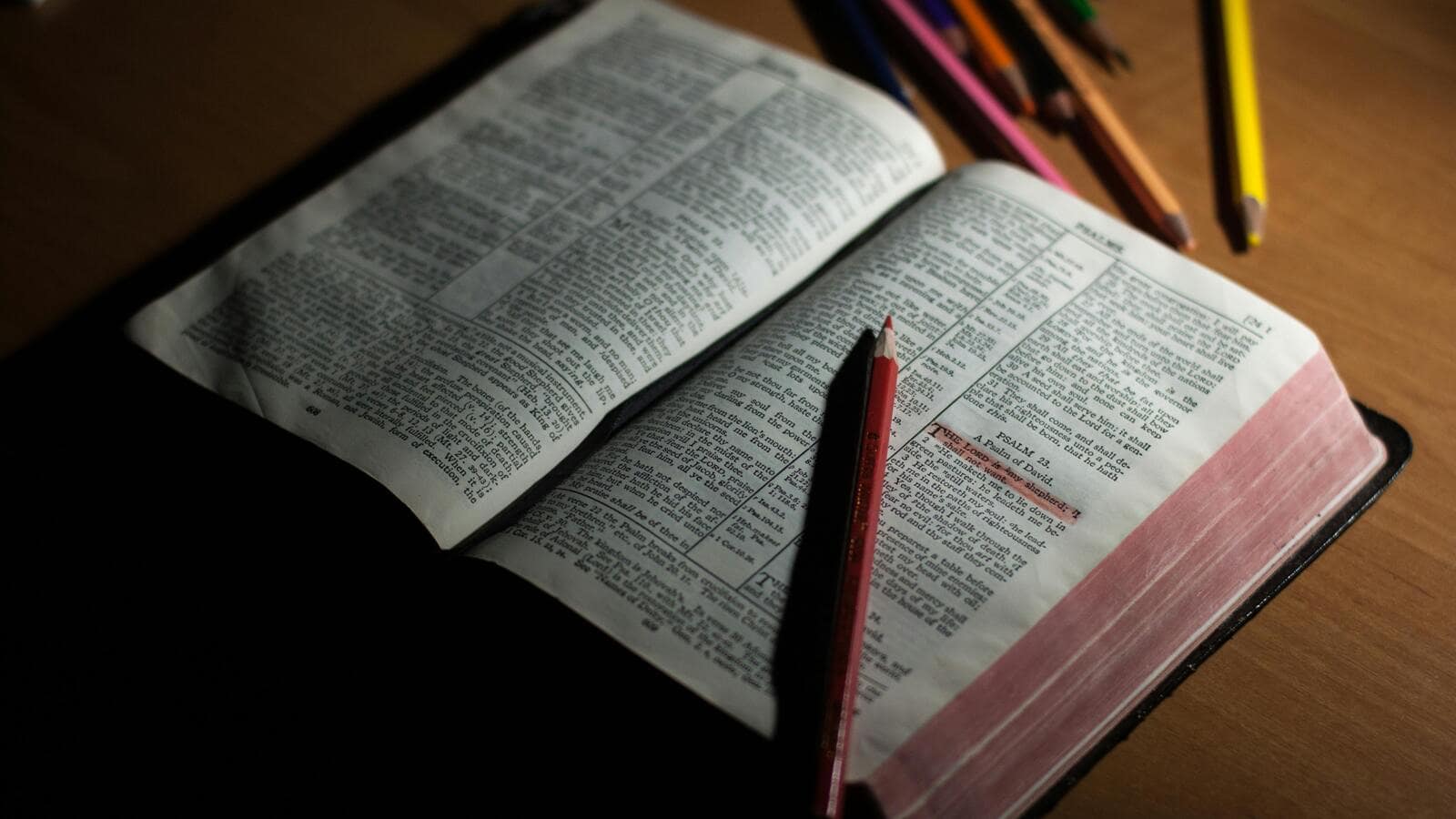

Have you ever walked into a bookstore to grab a Bible and felt completely overwhelmed by the sheer number of options on the shelf? You might pick one up thinking it is just a standard copy, only to realize later that it has more pages or different books than the one your neighbor reads. It is a common confusion because these two major Christian traditions actually use different collections of scripture.

While both groups agree on the core story of Jesus and the New Testament, they differ significantly in how they organize and define the Old Testament. This divergence stems from centuries of history, theology, and debates about which ancient texts truly belong in the canon. Understanding these variations helps explain why your friend’s Bible might be thicker or have slightly different wording than yours.

The Total Number Of Books In The Canon

The most obvious distinction you will notice right away is the simple math involved in counting the contents of each book. A standard Catholic Bible contains 73 books, while a Protestant version typically lists only 66. This difference is not just a printing error but a fundamental disagreement about which texts are divinely inspired.

Catholic Bibles maintain forty-six books in the Old Testament, preserving a wider range of ancient writings used by early Christians. Protestant Bibles, on the other hand, strictly follow the Jewish canon for the Old Testament, which limits that section to thirty-nine books. This decision to slim down the collection occurred largely during the Reformation, to align more closely with the Hebrew scriptures.

The Inclusion Of The Apocrypha Or Deuterocanon

You might open a Catholic Bible and stumble upon books like Tobit, Judith, or First and Second Maccabees that you cannot find in a King James Version. Catholics refer to these seven additional books as the Deuterocanon, meaning “second canon,” and treat them as equal scripture. These texts offer history and wisdom that bridge the gap between the Old and New Testaments.

Protestants usually label these texts as the “Apocrypha,” a term that suggests they are hidden or of doubtful origin. While some Protestant editions print them in a separate section for historical interest, they are rarely considered authoritative for establishing doctrine. According to Lifeway Research, the American Bible Society estimates that about 41% of Americans qualified as “Bible Users” in 2025, yet many remain unaware of these distinctions.

The Differing Views On Biblical Authority

For Protestants, the Bible stands alone as the ultimate source of truth, a concept known historically as Sola Scriptura. This means that if a tradition or teaching contradicts the written text, the text must always win the argument. Consequently, Protestant study Bibles often focus heavily on individual interpretation and cross-referencing scripture with scripture.

Catholics view the Bible as one part of a dual authority structure alongside Sacred Tradition. They believe that the Church’s teaching authority, or Magisterium, is necessary to correctly interpret the Bible and prevent errors. This approach means a Catholic reader relies on the Church to guide their understanding of complex passages rather than going it alone.

Variations In The Ten Commandments Numbering

If you compare a catechism from both traditions, you might be surprised to see the Ten Commandments listed in a different order. Catholics generally combine the command against worshipping other gods with the prohibition on idols, making them the first commandment. To keep the number at ten, they then split the final command against coveting into two separate parts: coveting a neighbor’s wife and coveting their goods.

Protestant traditions usually separate the command against other gods and the command against making graven images into the first and second commandments. This shift means that the numbering for every subsequent commandment is off by one compared to the Catholic listing. It is a subtle theological shift that emphasizes the distinct danger of idolatry.

The Philosophy Behind Translation Styles

Translation committees for each tradition often approach the ancient languages with slightly different priorities and constraints. Catholic Bibles typically require an official approval, known as an Imprimatur, which certifies that the text aligns with Church doctrine. This ensures consistency but can sometimes limit the variety of paraphrased versions available to Catholic readers.

Protestant publishers have the freedom to produce a massive array of translations ranging from rigid word-for-word renderings to loose, modern paraphrases. According to Pew Research, Protestants make up 40% of the U.S. adult population, creating a huge market for diverse translation styles. This open market allows niche Bibles targeting specific demographics, such as teenagers or busy professionals, which is less common in Catholicism.

The Necessity Of Explanatory Footnotes

When you read a Catholic Bible, you are almost guaranteed to find notes at the bottom of the page explaining difficult verses. Canon Law actually requires that editions of the Bible published for Catholics include explanatory notes to guide readers. The goal is to ensure personal interpretation does not drift from established theological truths.

Protestant Bibles vary wildly in this regard, with some “text-only” editions offering zero commentary and others providing thousands of study notes. A Gallup poll recently found that only 20% of Americans believe the Bible is the literal Word of God, suggesting many readers look for context. Protestant notes often focus on historical data or practical application rather than doctrinal conformity.

The Ending Of The Lord’s Prayer

Attend a service in both churches, and you will notice a jarring difference when the congregation recites the Lord’s Prayer. Protestants almost always end the prayer with the doxology: “For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, forever.” This familiar conclusion is found in some later manuscripts of the Gospel of Matthew but was likely not in the original text.

Catholic Bibles and liturgy omit this final sentence from the prayer itself, pausing before the priest speaks it separately in the Mass. Scholars generally agree that the line was a liturgical addition by the early church rather than words Jesus spoke directly. This commitment to the earliest manuscript evidence creates a small but noticeable gap in Sunday worship practices.

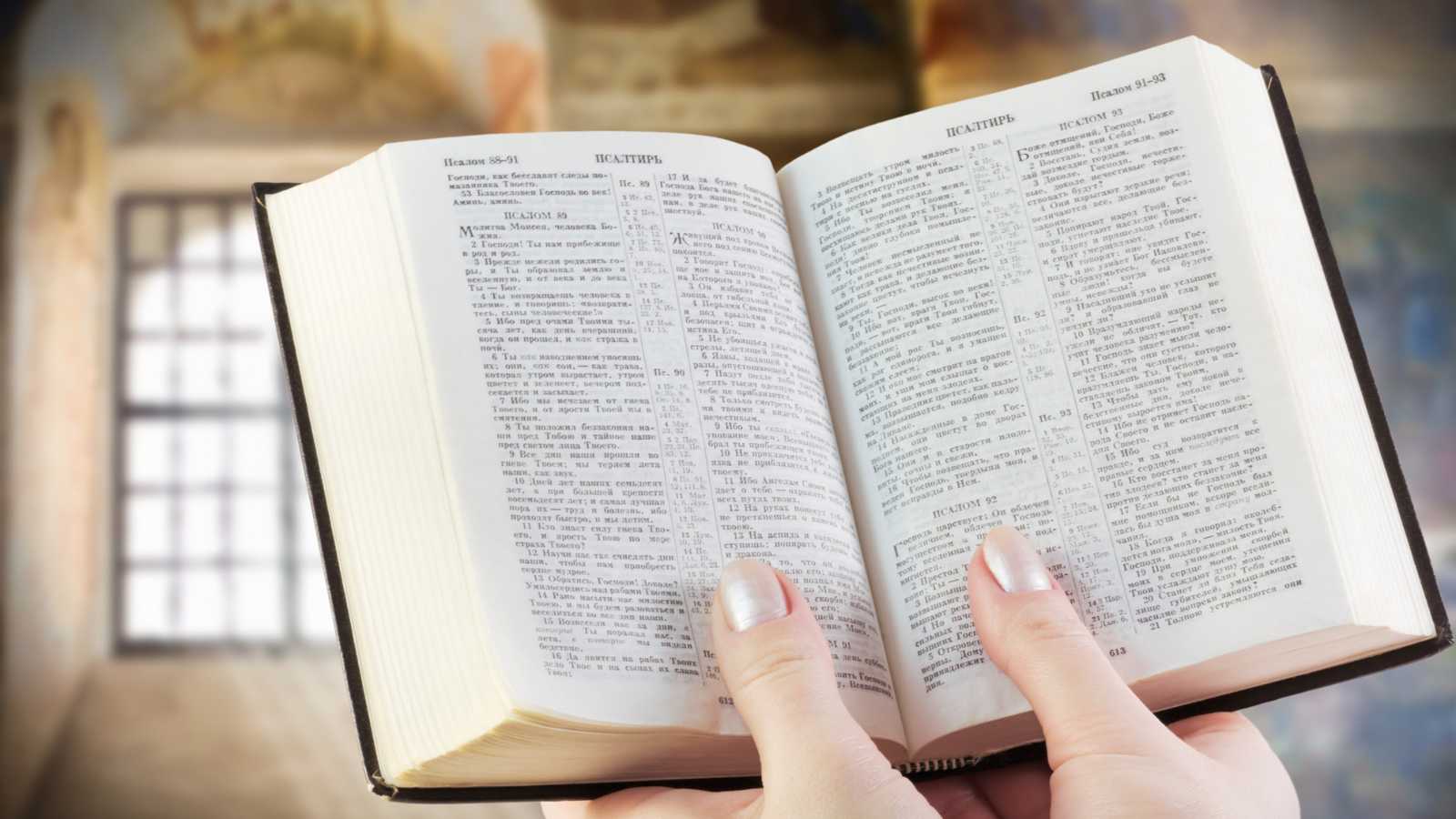

The Language Of The Old Testament Source Text

The roots of these differences lie in the ancient source texts the translators prioritized throughout history. Catholic Bibles traditionally relied on the Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Old Testament widely used by Jesus and the apostles. This Greek collection included those seven extra books we mentioned earlier, cementing their place in the early Church.

Protestant reformers decided to return to the Masoretic Text, which is the Hebrew version of the scriptures maintained by Jewish scholars. Since the Masoretic Text did not include the seven deuterocanonical books, the Reformers removed them to match the Hebrew canon. Lifeway Research notes that 66% of Evangelicals believe the resurrection is completely true, showing how deeply they trust this specific canon of scripture.

The Role Of The Magisterium In Interpretation

A Catholic Bible is rarely viewed as a standalone book that you can interpret entirely on your own terms. The Church teaches that the Magisterium, consisting of the Pope and bishops, has the sole authority to interpret scripture authentically. This safeguards the community from fracturing into thousands of groups with conflicting beliefs about the same verses.

Protestantism encourages individual believers to read and interpret the Bible for themselves, trusting the Holy Spirit for guidance. This freedom has led to the formation of thousands of denominations, as people disagree over the meaning of specific passages. It reflects a cultural shift toward individualism that resonates with the 57% of Americans who are now “Bible Disengaged,” according to the American Bible Society.

Differences In Liturgical Readings And Structure

How the Bible is read aloud during church services also varies significantly between the two traditions. Catholic churches follow a three-year cycle called the Lectionary, ensuring the congregation hears nearly the entire Bible over that period. This structured approach means every Catholic church in the world reads the same scriptures on the same day.

Protestant churches often follow the pastor’s choice, meaning a sermon series might stay in one book for months. While some mainline denominations use a lectionary, many evangelical churches prefer a “verse by verse” or topical approach. With 66% of Bible users now accessing scripture digitally, the way people follow along with these readings has shifted dramatically in recent years.

Disclosure: This article was developed with the assistance of AI and was subsequently reviewed, revised, and approved by our editorial team.

Like our content? Be sure to follow us