15 school facts you learned that are no longer considered true

Remember that feeling of certainty in school, when the textbook was the ultimate source of truth? Well, it turns out a lot of those “truths” had an expiration date.

It’s a wild thought, but facts have a shelf life. Scientists even have a term for it: the “half-life of facts.” It’s the idea that over time, about half the knowledge in any given field gets disproven or becomes obsolete. For example, in Samuel Arbesman’s excellent book The Half-life of Facts: Why Everything We Know Has an Expiration Date, the half-life for medical facts about liver diseases like hepatitis was 45 years—meaning half of what doctors thought they knew was outdated just a few decades later.

This churn of information is why textbook publishers release new editions every three to four years; knowledge, especially in science, moves so fast that a book can be outdated before the ink is dry.

The world of science and history is constantly moving, and it means much of what we accepted as gospel in the classroom has been completely overturned by new discoveries. This isn’t a knock on our teachers; it’s proof that we’re always learning. So, let’s update our mental software and catch up on a few things that have changed since we last sat at a desk.

You have only five senses

Remember learning about sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch? That neat little package of five senses has been the standard since Aristotle first laid it out thousands of years ago.

But that tidy model is a massive oversimplification. Neuroscientists now argue that humans have anywhere between 22 and 33 different senses. Our experience of the world is way richer than the “big five” suggests.

You’re using these extra senses all the time without even thinking about it. Ever typed on a keyboard without looking? That’s proprioception, your brain’s sense of where your body parts are in space. The feeling that keeps you from toppling over is equilibrioception, your sense of balance. You also have thermoception (sensing temperature) and nociception (feeling pain).

The real mind-bender is how they all work together. British philosopher Barry C. Smith points out that Aristotle missed how our senses interact to create new experiences. This “multisensory perception” is why food tastes bland when you have a cold (smell affects taste) or why you feel like you’re moving up on an airplane at takeoff, even when you’re just looking at the seat in front of you (your sense of balance is altering your vision).

The tongue is mapped into different taste zones

We all saw that colorful diagram in our science textbooks: sweet at the tip, bitter at the back, with salty and sour on the sides. It was a simple, easy-to-memorize “fact.” Except, the tongue map is a complete myth. As neuroscientist Brian Lewandowski from the Monell Chemical Senses Center puts it, “The tongue does not have different regions specialized for different tastes. All regions of the tongue that detect taste respond to all five taste qualities.”

The whole misunderstanding began with a 1901 paper by a German scientist who noted that certain parts of the tongue were slightly more sensitive to specific tastes. But his nuanced findings were misinterpreted by a Harvard psychologist, who created the oversimplified map we all know.

The reality is that every single one of your taste buds—which are all over your tongue, the roof of your mouth, and even your throat—can detect all five tastes: sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and the savory taste known as umami.

Pluto is the ninth planet in our solar system

Many of us can still recite the mnemonic we used to memorize the nine planets: “My Very Educated Mother Just Served Us Nine Pizzas.” For over 75 years, Pluto was our solar system’s icy, distant underdog. Then, in 2006, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) voted to reclassify it as a “dwarf planet.” But why the sudden change? It wasn’t that Pluto changed; our understanding of space did.

Pluto got demoted because it failed to meet one of three new criteria for being a planet: it hasn’t “cleared the neighborhood around its orbit.” This means it isn’t the main gravitational force in its path. Instead, it shares its orbit with lots of other icy objects in a region called the Kuiper Belt.

The real tipping point was the discovery of Eris in 2005, a celestial body in the Kuiper Belt that was even more massive than Pluto. Astronomers realized they’d either have to add Eris and dozens of other objects to the planet list or redefine what a planet is. They chose to redefine. The debate isn’t over, though. Some astronomers point out that even Earth shares its orbit with thousands of asteroids, questioning whether any planet truly “clears its neighborhood.”

Christopher Columbus discovered America

“In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue” is a rhyme we all learned, painting a simple picture of a brave explorer finding a “New World.”

This narrative is wrong on almost every level. First and foremost, you can’t “discover” a place that’s already home to millions of people. When Columbus arrived, the Americas were inhabited by an estimated 40 million Indigenous people with thriving civilizations that had existed for tens of thousands of years.

Second, he wasn’t even the first European to make the trip. Norse explorers like Leif Eriksson landed in Canada nearly 500 years earlier, around 1000 AD. And third, Columbus never even set foot in North America. His voyages took him to Caribbean islands and the coasts of Central and South America.

Today, historians are reframing the story from one of “discovery” to one of “contact”—a contact that led to enslavement, brutality, and the spread of diseases that devastated Indigenous populations. This shift acknowledges a more painful and complex history, one in which Columbus himself wrote of the native Taíno people, “They should be good servants.”

The food pyramid is the best guide to healthy eating

For years, the food pyramid was the ultimate symbol of healthy eating, with its wide base of bread, cereal, rice, and pasta.

However, that pyramid was dismantled by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) in 2011. It was subsequently replaced by a simpler visual representation: MyPlate. The old pyramid had some major flaws. It was based on outdated science that recommended a whopping 6-11 servings of carbohydrates a day, without distinguishing between healthy whole grains and processed white bread.

MyPlate offers a more balanced and intuitive guide. The new model is a simple plate, visually divided into four sections: half your plate should be fruits and vegetables, and the other half should be split between grains and protein, with a serving of dairy on the side. It’s a straightforward reminder of what a healthy meal should actually look like.

Goldfish have a three-second memory

It’s a classic joke and a convenient excuse for keeping a fish in a tiny bowl: the idea that a goldfish forgets everything every three seconds.

In reality, this is a complete myth that has been debunked for over 60 years. Studies have shown that goldfish can remember things for at least five months. They are so good at learning, in fact, that they’re often used in scientific studies on memory. Researchers have successfully taught goldfish to navigate mazes, press levers for food, and even distinguish between different pieces of music.

You are either a ‘left-brain’ or a ‘right-brain’ thinker

You’ve probably taken a quiz that labeled you as either a logical, analytical “left-brain” thinker or a creative, artistic “right-brain” type.

It’s a fun idea, but neuroscientists call it a “neuromyth.” While it’s true that some brain functions are centered in one hemisphere—language processing is typically on the left, while spatial attention is on the right—that doesn’t mean you have a dominant side that defines your personality.

A 2013 University of Utah study that scanned over 1,000 brains found no evidence of people being “left-brained” or “right-brained.” We use both hemispheres of our brains constantly.

The myth likely took hold because it offers a simple way to categorize ourselves and others. But the truth is far more interesting: our brains are incredibly complex, integrated organs where both sides work together constantly.

Diamonds are just chunks of coal under pressure

It’s a beautiful metaphor: a worthless lump of coal transforms into a brilliant diamond under pressure. It’s a story we’ve seen everywhere, from inspirational posters to Superman comics, where the hero crushes coal in his hand to make a diamond.

Unfortunately, this story is geologically impossible. The main reason? Age. Most diamonds are billions of years old, meaning they formed long before the Earth’s first land plants even existed. And those plants are the essential ingredient for coal.

Diamonds are pure carbon that crystallized under immense heat and pressure about 90 miles deep in the Earth’s mantle. They were then shot to the surface in rare volcanic eruptions. Coal, on the other hand, is a sedimentary rock formed from compressed plant matter, and it’s rarely found more than two miles deep.

Vikings charged into battle wearing horned helmets

Picture a Viking. Chances are, you imagined a burly warrior with a beard and a helmet sporting a pair of menacing horns. It’s an image that’s been burned into our minds by cartoons, movies, and even football team logos. But it’s completely wrong. Archaeologists have never found a single Viking-era helmet with horns.

The only complete Viking helmet ever discovered, found on a farm in Gjermundbu, Norway, is a simple iron cap with a nose and eye guard—practical, protective, and decidedly horn-free. The horned helmet myth was born in the 1800s, when artists and costume designers for Richard Wagner’s operas wanted to create a more dramatic and romantic image of the Norse raiders. While horned helmets did exist, they were from the Bronze Age, nearly 2,000 years before the Vikings—and were likely used for ceremonial purposes, not for battle.

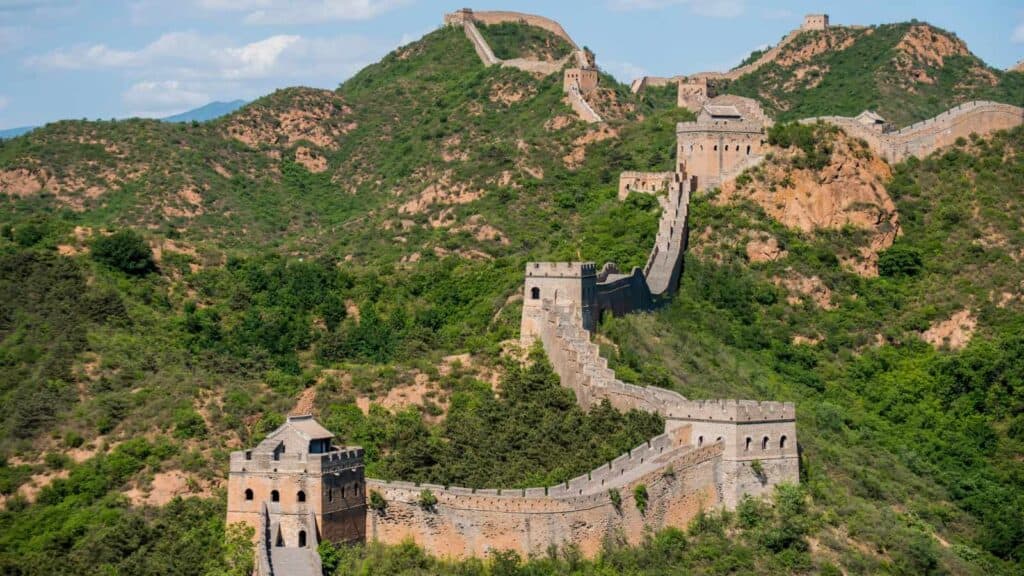

The Great Wall of China is the only man-made object visible from space

This “fact” has been a staple of trivia nights and school textbooks for decades, a testament to human ingenuity.

The only problem is, it isn’t true. In fact, according to NASA, the Great Wall is “difficult or impossible to see from Earth orbit” with the naked eye.

The reason is simple physics. The wall, while incredibly long, is only about 20-30 feet wide. Its color and materials also blend into the surrounding landscape. Trying to see it from low orbit has been compared to trying to spot a 2-centimeter-wide cable from more than half a kilometer away.

Human evolution was a straight march of progress

You know the image: a line of figures starting with a hunched-over ape, gradually standing more upright until you get to a modern human. It’s called the “March of Progress,” and it’s probably the most famous depiction of evolution.

It’s also completely misleading. Evolution isn’t a straight line heading toward a perfect endpoint (us). It’s more like a sprawling, branching tree with countless dead ends and winding paths. Humans did not evolve from the apes we see today; rather, humans and modern apes share a common ancestor that lived millions of years ago. That famous illustration, created for a 1965 Time-Life book, reinforces the arrogant and incorrect idea that humans are the “pinnacle” of evolution.

Glass is secretly a very slow-moving liquid

This is a charming one. The reason old stained-glass windows in medieval cathedrals are thicker at the bottom is that glass is an incredibly slow-moving liquid, and it has sagged over the centuries.

It’s a great story, but it’s just an urban legend. Glass is an amorphous solid, not a liquid.

The unevenness you see in old glass panes has nothing to do with flow. It’s a leftover from primitive glass-making techniques. As MIT materials science professor Michael Cima puts it, “That’s just not true. The windows were made that way.” Before modern methods, glass was made by blowing it into large cylinders or spinning it into discs, which resulted in panes that were never perfectly flat or uniform.

Lemmings commit mass suicide

The image of hordes of tiny lemmings blindly following each other off a cliff into the sea is one of nature’s most bizarre and enduring myths. It’s also a complete fabrication, courtesy of a 1958 Disney nature documentary called White Wilderness.

The filmmakers wanted to capture dramatic footage of the lemmings’ famed population cycles. But when nature didn’t cooperate, they took matters into their own hands. The crew bought a few dozen lemmings, flew them to a cliff overlooking a river in Alberta, Canada (nowhere near the Arctic Ocean), and literally herded them off the edge to their deaths.

In reality, lemming populations do explode every few years, leading to mass migrations in search of food. During these migrations, some may accidentally fall from cliffs or drown while trying to cross rivers, but it is never intentional suicide.

Napoleon Bonaparte was a very short man

The term “Napoleon complex” exists for a reason: to describe a shorter man compensating with an aggressive, power-hungry personality. The French emperor has gone down in history as famously short.

But he wasn’t. Napoleon was actually about 5’6″, which was an average, or even slightly above-average, height for a Frenchman in the early 1800s. The myth comes from two main sources. First, a mix-up in measurement systems; his height was recorded as 5’2″ in French units, but the French foot was longer than the British foot, leading to confusion.

Second, and more importantly, it was a deliberate propaganda campaign by the British. Cartoonists like James Gillray mercilessly mocked the emperor, portraying him as a tiny, tantrum-throwing child they nicknamed “Little Boney.” The image stuck, proving that a good caricature can be more powerful than the truth.

Albert Einstein failed his math classes

It’s the ultimate comfort for any student struggling in school: even the great Albert Einstein was a bad student who flunked math.

This is perhaps one of the most persistent and completely false myths in modern history. Einstein was a math prodigy from a very early age.

His school records prove it. His matriculation certificate from 1896 shows he earned the highest possible grade (a 6 out of 6) in both algebra and geometry.

Time reports that when a rabbi once showed him a “Ripley’s Believe It or Not!” column with the headline “Greatest living mathematician failed in mathematics,” Einstein just laughed. “I never failed in mathematics,” he said. “Before I was fifteen, I had mastered differential and integral calculus.” The myth likely survives because we love a good story about an underdog who blossoms late—even if, in this case, it’s not true.

Why investing for retirement is so important for women (and how to do it)

Why investing for retirement is so important for women (and how to do it)

Retirement planning can be challenging, especially for women who face unique obstacles such as the wage gap, caregiving responsibilities, and a longer life expectancy. It’s essential for women to educate themselves on financial literacy and overcome the investing gap to achieve a comfortable and secure retirement. So, let’s talk about why investing for retirement is important for women and how to start on this journey towards financial freedom.