Umami: The Fifth Taste Sensation

You have probably heard of the taste sensations sweet, salty, sour, and bitter. But did you know that there is a fifth flavor? It’s umami, and maybe you have heard it mentioned, but have never quite understood what it is. If you are a food lover as we are, understanding umami might broaden your understanding and appreciation of food, so let’s dive in.

Umami Defined

Umami, a term originating from Japanese cuisine, embodies the concept of “pleasant savory taste” or simply, “deliciousness.” Often likened to a meaty essence, umami tantalizes the taste buds with its robust and satisfying flavor profile. While widely recognized in Asian culinary traditions, its acknowledgment in Western gastronomy has been less popularized and understood.

Umami Discovered

The genesis of umami traces back to 1908 when Japanese scientist Kikunae Ikeda embarked on a quest to decipher the essence of dashi, a traditional Japanese broth made from seaweed and dried fish flakes, which is known for its bold, meaty flavor.

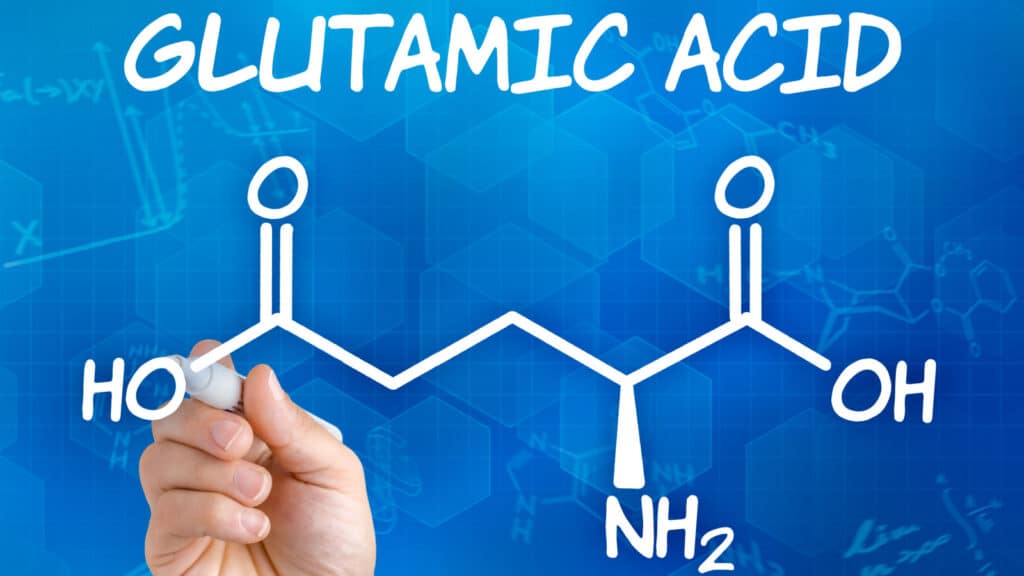

His experiments yielded crystals via an evaporation process. He detected the distinct, meaty, savory flavor in the crystals, and named it umami from the Japanese word “umai” meaning “delicious”. The molecular formula was the same as the amino acid glutamic acid, which in humans presents as glutamate, a similar compound that has one less hydrogen atom.

Glutamate is one of the most plentiful excitatory neurotransmitters in our brains. Simply put, it is a chemical that helps nerve cells in the brain send and receive information from other cells. By 1909 Ikeda began selling his crystal product, Ajinomoto, (meaning “essence of taste”) as a flavor enhancer – and yes, it is indeed MSG, otherwise known as monosodium glutamate.

The Science Behind Umami

The umami savory, meaty taste sensation originates from three naturally occurring compounds: glutamate, inosinate, and guanylate. Glutamate, the first compound, is an amino acid abundant in vegetables and meat. Inosinate is predominantly found in meat, whereas guanylate levels are highest in plants. When consuming foods rich in glutamate, this compound interacts with receptors on the taste buds, eliciting the savory sensation.

Glutamate exists in two forms: bound to other amino acids in proteins and in a free or unbound state. It’s the free glutamate that contributes to the umami taste sensation.

MSG & Umami

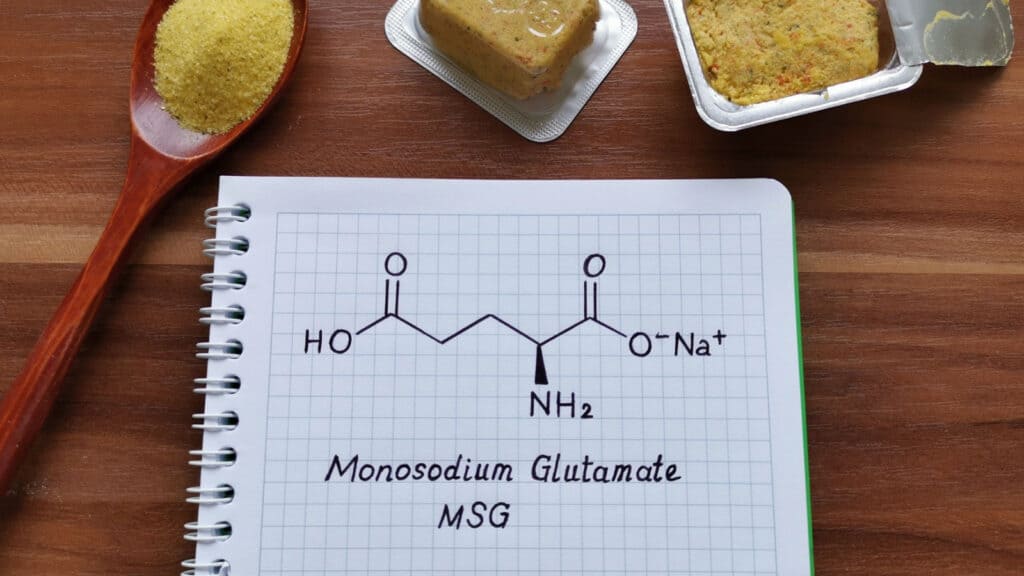

Umami and monosodium glutamate (MSG) are often associated with each other due to their connection through Ikeda, who discovered umami and created MSG. Initially, umami wasn’t recognized as a distinct taste, but was rather conflated with MSG. However, in the late 20th century science confirmed umami as the fifth basic taste, separate from salty, bitter, sweet, and sour.

Unlike umami, which occurs naturally in foods rich in glutamate, MSG is a synthesized additive created to enhance the umami flavor in dishes. MSG can be a valuable tool in reducing sodium levels in foods while still enhancing flavor, which can be beneficial for those on low-sodium diets.

How To Detect MSG on Labels

MSG can be listed under various names on food labels, such as glutamate, hydrolyzed protein, autolyzed yeast, or yeast extract, among others. However, these alternative names do not change its basic function as an enhancer of umami taste.

And then of course, as the image above illustrates, you can buy pure MSG to add to food.

Is MSG Dangerous?

MSG is not dangerous. There are studies that have explored MSG’s toxicity and effect on humans and animals. In large amounts it has been associated with obesity, insulin resistance, hepatic damage, and gastric distension. Please note that amounts were copious.

And then there is “Chinese restaurant syndrome” (CRS), which was first referenced in 1968. “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome” refers to a set of symptoms described as numbness in the neck, arms, and back, accompanied by headache, dizziness, and palpitations, believed to affect certain individuals after consuming Chinese cuisine heavily seasoned with monosodium glutamate.

Although the term was officially recognized in Merriam-Webster’s dictionary in 1993, it had been circulating in American culture for decades prior. And by the way, Merriam-Webster altered the entry to now notate it as dated and “offensive”, as it is seen as a racist term. It has been replaced in medical literature by “MSG symptom complex”.

The origin of this syndrome can be traced back to a 1968 letter published in the New England Journal of Medicine, alleging that Chinese food consumption led to various health issues. Despite later revelations that the letter was a hoax, the misconception persisted. The US Food and Drug Administration has consistently approved MSG for consumption, and scientific studies have failed to establish a causal link between MSG and the reported symptoms. No scientifically accepted mechanism for harm has been identified. A comprehensive review of scientific literature published in the journal Food Science and Food Safety in 2019 concluded that the assertions linking MSG to various health problems lack substantiation.

The Complexity of Taste & Flavor

You may not have thought about it before but very often foods that we deem “complex” are often a balance of the 5 tastes – having more than one taste type in one food makes for a multifaceted experience.

On the other hand, sometimes we like to have a more mono experience, as with potato chips, where saltiness is predominant. Neither taste sensation is better than another – we are just giving you a vocabulary for understanding taste in food.

Umami-Rich Foods

Many foods are known to be naturally rich in umami, such as:

- Several cheeses, particularly Parmigiano Reggiano and blue cheese such as Roquefort

- Meats and poultry

- Soy sauce, Worcestershire sauce, fish sauce and oyster sauce

- Fish and shellfish; anchovies are a good choice

- Tomatoes, particularly when concentrated such as in tomato paste, or sun-dried tomatoes

- Miso

- Vegemite and Marmite

- Nutritional yeast (our favorite is Bragg’s).

- Walnuts

- Seaweed such as kombu

- Fresh mushrooms

- Dried shiitake mushrooms

Elevating Umami Through Culinary Techniques

Beyond ingredient selection, culinary techniques can greatly amplify umami notes. Caramelization, for instance, intensifies the savory depth of ingredients like tomatoes, while fermentation accentuates umami complexities in products like miso (shown above). Similarly, aging and curing processes heighten umami nuances in meats and cheeses, lending complexity.

The Takeaway

Ultimately, incorporating umami-rich foods into your cooking can elevate the flavor profile of your dishes, providing a satisfying and delicious culinary experience. You have probably been cooking with and enjoying umami even if you didn’t realize it! Now you know.