Darwin nearly quit the voyage that changed science

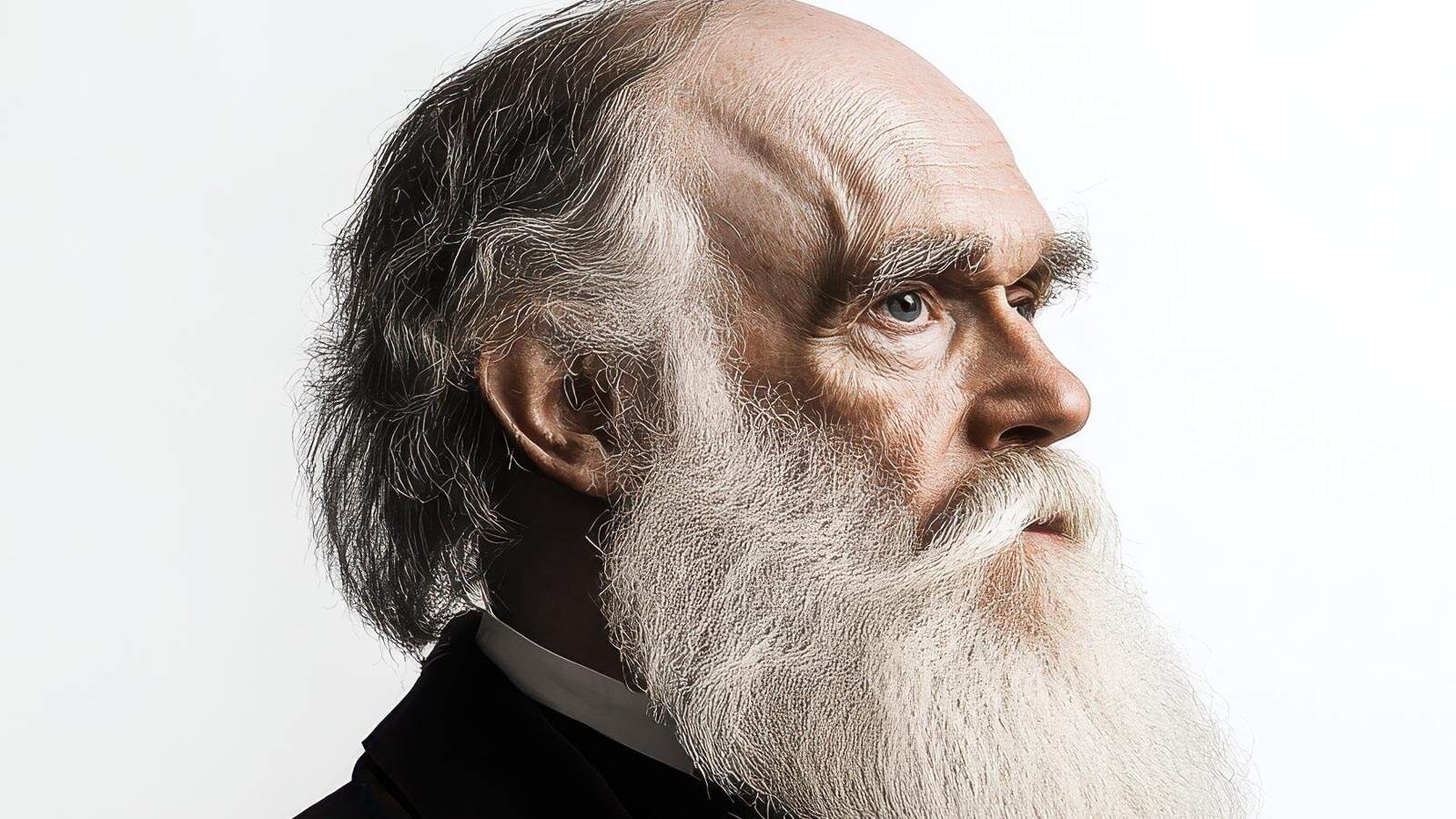

Before he became the calm, bearded icon of science, Charles Darwin was a miserable, seasick 22-year-old just trying to survive a voyage he almost didn’t take.

Charles Darwin’s five-year voyage on the HMS Beagle remade science, but it nearly broke him first. Behind the later image of the bearded sage was a 22‑year‑old prone to violent seasickness, crushing headaches, mysterious heart palpitations, and waves of self‑doubt that left him questioning whether he should have gone at all. Trapped between a tiny cabin and a volatile captain, he filled his days with collecting, sketching, and scribbling frantic diary entries that veered from wonder to despair.

Yet those same frailties sharpened his eye and slowed his pace, forcing him to linger on coasts and in backcountry landscapes where he saw — and wrote down — the clues that would later become his theory of evolution by natural selection. The voyage that rewrote humanity’s place in the universe was also, very much, the story of one anxious young man trying to keep his stomach — and his nerve — under control.

A Reluctant Adventurer

In the winter of 1831, Charles Darwin was an obscure recent graduate from Cambridge, more interested in beetles and country walks than in any grand scientific crusade. The Beagle opportunity came to him almost by accident: Captain Robert FitzRoy wanted a gentleman companion and unofficial naturalist on a surveying mission that might last several years. To Darwin’s family, it sounded like a dangerous distraction from a respectable career in the Church, and even he worried the voyage might prove “disreputable” to his future as a clergyman and that the whole scheme was “wild.”

Those early doubts set the emotional tone. He knew the ship was small, the mission long, and the seas rough, and he already had a history of debilitating motion sickness from earlier crossings of the English Channel. As he waited in Plymouth for the Beagle to sail, he experienced chest pain and “palpitations and pain around the heart,” but said nothing for fear the symptoms would cost him the berth. The man who would later challenge Victorian certainties almost didn’t board the ship that made it possible.

The Beagle finally departed in late December 1831, a compact vessel crammed with men, instruments, and provisions. Darwin secured a makeshift corner near the chart room for his hammock, books, and collecting gear — a space that would double as his sickbed for years. Almost immediately, his body rebelled.

Seasickness Without End

From the first heavy seas in the Bay of Biscay, Darwin was overwhelmed by violent seasickness that became a defining feature of his life at sea. In his Beagle diary, he later wrote that “the misery I endured from seasickness is far beyond what I ever guessed at,” adding that if not for seasickness, “the whole world would be sailors.” For days at a time, he lay in his swaying hammock, barely able to eat more than biscuits and raisins, too ill to read or write.

This was not the passing nausea of a few rough days. Modern medical historians see his severe and persistent motion sickness as part of a broader, recurring illness that dogged him before, during, and after the voyage. During the Beagle years, he experienced repeated bouts of prostrating exhaustion, pounding headaches, stomach upsets, and spells of weakness that left him unable to stand. One account notes that, even on land later in life, “motion sickness was present throughout his life” and that he himself blamed his “four-year bout with seasickness” on the Beagle for much of his later poor health.

On shipboard, survival required adaptation. Darwin discovered that lying flat in his hammock was the only real relief, and he learned to seize the rare calm days to work furiously. When the sea was smooth enough, he collected plankton and marine life from nets and buckets, examining them as long as his stomach allowed. The rest of the time, he endured, writing of the indignation of having “all one’s efforts to do anything paralysed” by sickness.

The irony is stark: the man whose name became synonymous with hard-headed scientific toughness spent much of his great voyage half incapacitated, fighting his own body. Yet that weakness pushed him to find refuge where the ground stopped moving.

Landfalls, Fevers, and Self‑Doubt

Darwin’s salvation came whenever the Beagle anchored and put him ashore. While the ship’s officers surveyed coasts and harbors, he escaped inland: riding across pampas, climbing mountains, trudging through tropical forests. Over the course of the five‑year journey, he spent more than three years on land, often on strenuous excursions far from the ship.

The break from shipboard life brought its own hazards. In Brazil, Patagonia, and Chile, Darwin endured repeated bouts of fever, headaches, and gastrointestinal illness, sometimes linked to heat and overexertion. In Bahia in October 1833, he recorded “a violent headache, sickness, and shivering” that confined him to his hammock for three days while the ship’s surgeon dosed him with calomel and opium. In Valparaiso, Chile, he was bedridden for weeks with a severe illness that delayed the Beagle’s departure; he later suspected bad food from an inn had triggered it.

Exertion at altitude nearly undid him as well. During an ascent in the Andes, he wrote of shortness of breath and faintness so extreme that he had to lie down every few minutes, completely exhausted by the thin air. These episodes reinforced the sense that his body was unreliable, prone to collapse under stress.

Emotionally, he was just as fragile. Letters and diary entries from the voyage show a sensitive, self‑critical young man, vulnerable to anxiety, homesickness, and swings between elation and despair. He sometimes wondered whether he would ever “settle down to a steady life hereafter,” echoing early family worries that the voyage might unfit him for conventional respectability. At the same time, the raw intensity of tropical forests, the vast emptiness of the pampas, and the alien landscapes of volcanic islands left him breathless with awe. His illness heightened both the lows and the highs.

Living With a Volatile Captain

If Darwin’s body kept him off balance, the ship’s social world added another layer of tension. Captain Robert FitzRoy, a capable hydrographer and committed Christian, was also known for a fiery temper. He had originally planned to take a naval surgeon, Robert McCormick, as the principal naturalist, but Darwin’s enthusiasm and connections quickly made him the de facto scientific lead. McCormick resented the shift and left the voyage early, embittered by what he saw as his role being usurped.

This fraught reshuffling of status seeded conflicts. FitzRoy and Darwin clashed repeatedly, particularly over questions of slavery and Biblical interpretation. The captain, an aristocrat with conservative views, bristled at Darwin’s growing skepticism and his horror at the treatment of enslaved people in South America. Arguments on a cramped ship with no escape could burn hot, and Darwin, already prone to anxiety and fatigue, felt the strain.

Yet FitzRoy also gave Darwin extraordinary freedom to explore inland when the ship’s schedule allowed. The captain’s determination to chart coasts and harbors left Darwin with long windows away from the ship, time he filled with geological measurements, fossil hunting, and detailed natural history observations. The uneasy partnership between the devout captain and the doubting naturalist ended up shaping the intellectual outcome of the voyage: while FitzRoy measured the world’s coasts, Darwin measured the living world’s variation.

The Diary That Became a Turning Point

Darwin’s most important coping mechanism was his pen. From the earliest days of the voyage, he kept a detailed Beagle diary — now preserved and published — noting not only animals, rocks, and plants, but also his own reactions. In cramped handwriting, he documented sea conditions, illnesses, quarrels, and flashes of scientific curiosity.

Primary sources from this period capture his ambivalence. In one letter to his mentor John Henslow from Patagonia, he admitted, “My stomach [is] much deranged, and I feel weak and languid.” Yet in the same period, he was exulting over fossilized giant mammals and the behavior of armadillos and rheas. The diary pages shift rapidly between physical complaint and close observation, mirroring the tug‑of‑war between his frail body and restless mind.

He wrote with particular intensity when illness forced him to pause. In Valparaiso, while confined to bed with severe headaches and sickness, he still took note of how grateful he was for the ship’s surgeon, writing later to FitzRoy that he would “always remember with gratitude the care of Bynoe during my illness in Valparaiso.” Years later, in another letter, he described himself as suffering from “ill-health of a very peculiar kind” that made “all mental excitement” dangerous because it was followed by “spasmotic sickness,” a pattern that had begun during the Beagle voyage.

Those notebooks and letters became the raw material for his later publications. After returning to England in 1836, he mined his diary to produce a travel narrative initially published as part of FitzRoy’s official account, later reissued under his own name as Journal of Researches. Readers thrilled to stories of exotic animals and wild landscapes, mostly unaware of the nausea and self‑doubt between the lines.

Watching Ideas Emerge, One Specimen at a Time

The romance of the Beagle story often compresses Darwin’s insight into a single epiphany on the Galápagos. The reality, as his diary and correspondence show, was slower and messier. Darwin did visit the Galápagos in 1835 and collect finches, tortoises, and mockingbirds that differed from island to island. But he did not immediately see those birds as a textbook case of evolution; that understanding emerged only after he returned home and analyzed his specimens alongside others.

Even so, the seeds were there in his field notes. He recorded how similar species replaced one another from region to region, how fossil bones of extinct mammals in South America resembled living armadillos and sloths, and how island creatures seemed to be modified versions of mainland forms. On long rides across the pampas, he puzzled over the distribution of species; on isolated coasts, he measured layered rock formations and pondered the immensity of geological time.

Illness and enforced idleness may actually have helped. When too weak to scramble over rocks or haul specimens, he could still sit and think, re‑reading his own notes and drawing connections. Later in life, he worked in a similarly constrained fashion at Down House, planning his days around spells of sickness and using the quiet of invalidism to refine his arguments. The man whose theories demanded patience — tiny variations accumulating over vast stretches of time — learned patience the hard way, through his own body’s limits.

Homecoming and a Changed Worldview

By 1836, after almost five years of intermittent seasickness, tropical fevers, and emotional strain, Darwin was desperate to see England again. As the shores of Falmouth finally came into view that October, he was “thrilled” at the prospect of the voyage ending — and at a future where the ground did not roll beneath his feet. He never fully overcame his motion sickness; even later crossings by sea could trigger old symptoms. But he returned with shiploads of specimens, notebooks full of observations, and a mind transformed.

In the years after the voyage, his health remained fragile. He complained of persistent abdominal troubles, fatigue, and nervous symptoms that limited his ability to travel and socialize. Yet the Beagle experience had already done its work. The combination of physical vulnerability, isolation, and prolonged exposure to the diversity of life around the globe had chipped away at his earlier assumptions. His faith shifted; his scientific questions deepened.

When On the Origin of Species appeared in 1859, it landed in a world where Darwin was already known as the author of a vivid travel narrative and as a careful, if often ailing, naturalist. The book’s argument — that species are not fixed, but change through natural selection — drew heavily on examples from the Beagle years: creatures of the Galápagos, fossils from South American riverbeds, plants and animals observed on far‑flung coasts. The voyage that had once seemed a “wild scheme” became, in retrospect, the foundation of a scientific revolution.

The Human Face of a Scientific Icon

It is tempting to see Darwin as the archetypal rational hero, serenely applying logic to nature. The Beagle story complicates that image. The primary sources from the voyage — his diary, letters, and the later recollections of those who sailed with him — reveal a young man repeatedly overwhelmed: by the roll of the ship, by illness, by the moral shock of slavery, by the sheer scale of the world.

Yet those human frailties are inseparable from his achievement. Seasickness drove him toward land, where he could observe more; his recurring illness forced him into reflective periods of note‑sorting and theorizing; his self‑doubt made him cautious, methodical, and hungry for evidence. The Beagle voyage did not turn a robust adventurer into a great scientist. It turned a vulnerable, often miserable young man into someone who understood, more deeply than most, how contingent and precarious life can be.

In that sense, “Darwin the human being” and “Darwin the revolutionary thinker” are the same person. The voyage that rewrote our place in the universe is also the story of how one person, plagued by seasickness and uncertainty, learned to trust what he saw with his own eyes.

What Fossils Reveal About Our Future On Earth

In the quiet layers of rock, footprints, bones, and leaves tell a story of worlds lost, and of our own uncertain future.

Every year, National Fossil Day invites us to pause and think about the extraordinary clues that the Earth has left behind. Fossils might look like simple stones tucked away in a museum case or pressed into the side of a canyon wall, but they are much more than that. They are the storytellers of our planet, whispering secrets of creatures that once walked, swam, or flew across ancient landscapes. They remind us that our world has changed dramatically, and they show us how life has endured through upheaval after upheaval. Learn more.