Unfulfilled Promise: The Inspiring but Tragic Tale of President James Garfield

This essay is part of “(There is Nothing New) Under the Sun“ A monthly column of random, historical vignettes demonstrating that the more things change, the more they stay the same.

I cannot watch a national convention without thinking about our 20th president, James Abram Garfield, who took the stage at the Republican National Convention of 1880 to introduce and endorse presidential hopeful and fellow Ohioan John Sherman and ended the conference the republican candidate for the highest office in the land. Halfway through his eloquent nominating address, Garfield queried the crowd, “And now, Gentlemen of the Convention, what do we want?” To which the assembled multitude responded, “We want Garfield!” And who could blame them?

From Canal Worker To Commander In Chief

Garfield, thought to be the poorest president in history, rose to the loftiest from the lowest station in the American caste system of the late 19th century. He was the last of the American presidents born in a log cabin, the youngest of 5 children, to a virtually penniless widowed mother in the backwoods of Cuyahoga County, Ohio. Taunted by his peers for his life of poverty, Garfield found refuge in reading. Uninterested in farming, young James (who couldn’t swim) dreamt of a swashbuckling life as a sailor, but the only seafaring ship in port in Cleveland rejected his job application, so with his limited resources, he had to settle for a job guiding the mules who pulled the sledges down the Ohio and Erie Canal. Sadly, his ambitions for a life on the briny blue were dashed because he fell in so many times that he contracted malaria and had to return home to the care of his mother. Later, looking back on his childhood, Garfield said, “I never meet a ragged boy in the street without feeling that I may owe him a salute, for I know not what possibilities may be buttoned up under his coat.”1

During the course of his convalescence, 17-year-old James was persuaded by his mother to forgo his maritime dreams and to try a year of schooling, which he did, at the Geauga Seminary, where he took to the life of a student like a duck to water, supporting himself as a carpenter and teacher. His quick mind and endless energy earned him a place in a sort of a college prep school, Western Reserve Eclectic Institute (later Hiram College), a co-ed institution where he learned Greek and Latin and fell in love with a fellow student, Lucretia Randolph, while supporting himself as the school’s janitor and part time teacher of Greek. “I mean to make myself a man,” he said, “and if I succeed in that, I shall succeed in everything else.”1

Developing His Progressive Philosophical Aims

At 22, Garfield enrolled at Williams College in Massachusetts, from which he graduated Phi Beta Kappa after only two years and was named salutatorian. New England, with its abolitionist and suffragist traditions of activism, was the cradle in which young James began to think of the efficacy of politics as a machine for achieving his newly found philosophical aims. It is worth noting that a large part of his education included his embrace of all kinds of people outside of his very limited, underprivileged, unsophisticated Mid-Western experience, allowing him to legitimately present himself as a learned man of stature with a dash of cosmopolitan East Coast polish.

Upon graduation, he returned to Hiram College and, at the age of 25, was appointed principal of the school, married Lucretia at 26, won a seat for the local senate at 28, and passed the bar at 29. As if all this was not impressive enough, he and Lucretia started having the first of their seven children (5 of whom lived to impressive adulthoods), the American Civil War began as Abraham Lincoln won the presidency, and James was commissioned as a Colonel in the 42nd Ohio Regiment of the Union Army. “Of course I deprecate war,” Garfield said, “but if it is brought to my door the bringer will find me at home.”1

To The Battle Field

Sent to Kentucky to fight against a Confederate force larger than his own, Garfield positioned his troops in such a manner that the enemy believed themselves to be outnumbered and so retreated. In the only battle commanded personally by Garfield, the 18th Brigade, in tandem with the 40th Ohio Infantry, attacked the evacuating rebels and won, earning Garfield a promotion to brigadier general at the tender age of 30. After pulling Major General Ulysses Grant’s bacon out of the fire in the Battle of Shiloh, Garfield was sick and forced to return home, but insisted on going back to military duty, believing now that – boiled down to its essence – the war was a struggle against slavery.

Assigned Chief of Staff to Catholic General William Rosecrans, Garfield and the older man became very good friends, both being well educated and eloquent conversationalists. This association widened Garfield’s understanding and acceptance of unfamiliar religions, and Rosecrans trusted his young advisor completely, allowing him to conceive, devise and execute campaigns against the Confederates, a job Garfield performed with such success that he ended up his boss’ boss, saving the day at The Battle of Chickamauga. The Union victory cleared the way for Sherman’s march to the sea. Grant was promoted to commander in chief of the western armies and, instead of Garfield, replaced Rosencrans with someone else, thereby causing a problematic relationship between Garfield and Grant.

Onward To Congress By Request From Lincoln

While the war raged on Garfield, at the specific request of Abraham Lincoln, resigned his commission in the army to serve in Congress, although his oldest daughter had just died at the age of 3, leaving James with a “desolation of heart.”1 Unlike Lincoln, who listened to his better angels, Garfield believed that those who had tried to tear the union asunder should have their property confiscated, forfeit their Constitutional rights, and suffer exile and execution. Further, he found the idea of “commutation,” in which a wealthy individual might pay another to serve for him in the military, disgraceful, and lobbied successfully to terminate the practice.

Garfield was an excellent Congressman, and in addition to drafting the version of the national census we use today, he drafted legislation that established our Bureau of Education. He was concerned with racial injustice, mostly as it applied to voting rights, standing strong against the Southern Democrats when they attempted to defund and eliminate the personnel who oversaw the polls to make sure that black voters were not intimidated. Another obsession was the preservation of the Gold Standard; Garfield believed that our economy would be better served by gold than by the “greenbacks,” or paper money used to finance the Civil War. He spent many hours researching his interests in The Library of Congress and spoke on the floor of The House of Representatives on the topics that interested him so powerfully that he became a darling of the press as well as his colleagues within the Republican party.

Kismet or Karma?

Distant bells remind us of a young senator from Illinois who took the stage at the 2004 DNC and spoke so brilliantly that he catapulted himself to national attention and was elected President of the United States a mere 4 years later, because at this very moment of Kismet, as Garfield was preparing to go up a rung on the ladder and run for a Senate seat, he was tapped by his friend, Treasury Secretary John Sherman, to nominate him for president at the Republican National Convention of 1880, and as you already know, Garfield’s speech was so exceptional that he, himself, ended as the Republican candidate for President, a position for which he was eminently qualified.

Unlike present political runs for office, however, campaigning publicly for oneself was frowned upon, so Garfield hosted something akin to FDR’s Fireside Chats of the 1930s and welcomed people to meet and greets on his front porch in Mentor, Ohio. Thousands of citizens and many journalists came from far and near to visit and to hear him speak (in what has been described as a “melodious baritone voice.”), returning home to relate his presidential suitability to family, friends, and neighbors. Some estimates put his audience numbers at as many as 17,000 over the course of his “non-campaign,” the resounding success of which served, for better or worse, as the inspiration for future candidates to play a more public part in their own campaigns.

The People’s House

Everett Collection via Shutterstock

Just two decades after the start of the cataclysmic War Between the States, America was starting to emerge from her nightmare, poised on the threshold of The Second Industrial Revolution and all of the wealth and innovation of The Gilded Age, America’s 38 states let onto a gigantic western frontier that beckoned to pioneers, skyscrapers emerged in bustling urban areas, immigrants poured into the country seeking opportunity, Thomas Edison patented his incandescent light bulb, Mark Twain, Henry James, Emile Zola, Thomas Hardy, Anthony Trollop, and Dostoevsky were getting published, ground was broken for The Panama Canal, New York’s Metropolitan Museum opened at Fifth Avenue and 82nd Street, progress was in the air, and Garfield’s win – by less than one-tenth of one percent for the popular vote, the closest margin in history – was a victory custom made for the times.

In this era, The White House was truly “the people’s house,” and politicians and private citizens could wander in and ask favors and appointments from their president. Just as Garfield’s relationship with Ulysses S. Grant was damaged by Grant’s appointment of what Garfield felt was a less deserving and qualified candidate to be his wartime right hand man, New York republican senator Roscoe Conkling, famous for his bullying tactics with previous President (and Garfield comrade) Rutherford Hayes, tried hard to ram New Yorkers for government positions down Garfield’s throat, but Garfield wasn’t having any of it, and in fact, appointed a Conkling adversary to a coveted position instead of the senator’s preferred candidate.

The Die Is Cast

This caused friction within the party (although the press applauded his action), but the most severe result was that it upset a mentally disturbed man from Illinois named Charles Guiteau who saw the trouble between the two republicans as a threat to the party and the nation. His despair was exacerbated by the thought that, because he had spoken out in support of Garfield during the Non-Campaign, he was owed a job in Garfield’s administration, and was among the many who showed up at The White House several times to request that he be made ambassador to France, an outlandish and ridiculous application for which he was utterly unsuited in training, temperament, and language skills. Finally, Guiteau was banished from The White House and told that he was no longer welcome there. The die was cast. Guiteau started to stalk the president and follow his calendar of events in the papers. In a perverse and interesting side note, Guiteau’s speechifying “on behalf” of Garfield was, in point of fact, on behalf of Ulysses Grant, who was thought to be a shoe-in as the republican nominee. Guiteau simply crossed out Grant’s name and scribbled in Garfield’s. His narcissism caused him to believe that he had played a grand part in Garfield’s ascension to the Oval Office.

The Assassination

On July 2, just four months after taking office, Garfield was leaving from the Baltimore & Potomac Train Station for a weekend of rest out of town when Guiteau, who had read in the newspaper that he would be there, snuck up behind him and fired a shot that grazed Garfield’s arm. A second bullet, shot from a pearl handled pistol the assassin had chosen thinking it would look good in a museum celebrating his martyrdom some day in the future, entered the president’s back, knocking Garfield to the floor. Guiteau was arrested, and doctors summoned. Ten doctors answered the call.

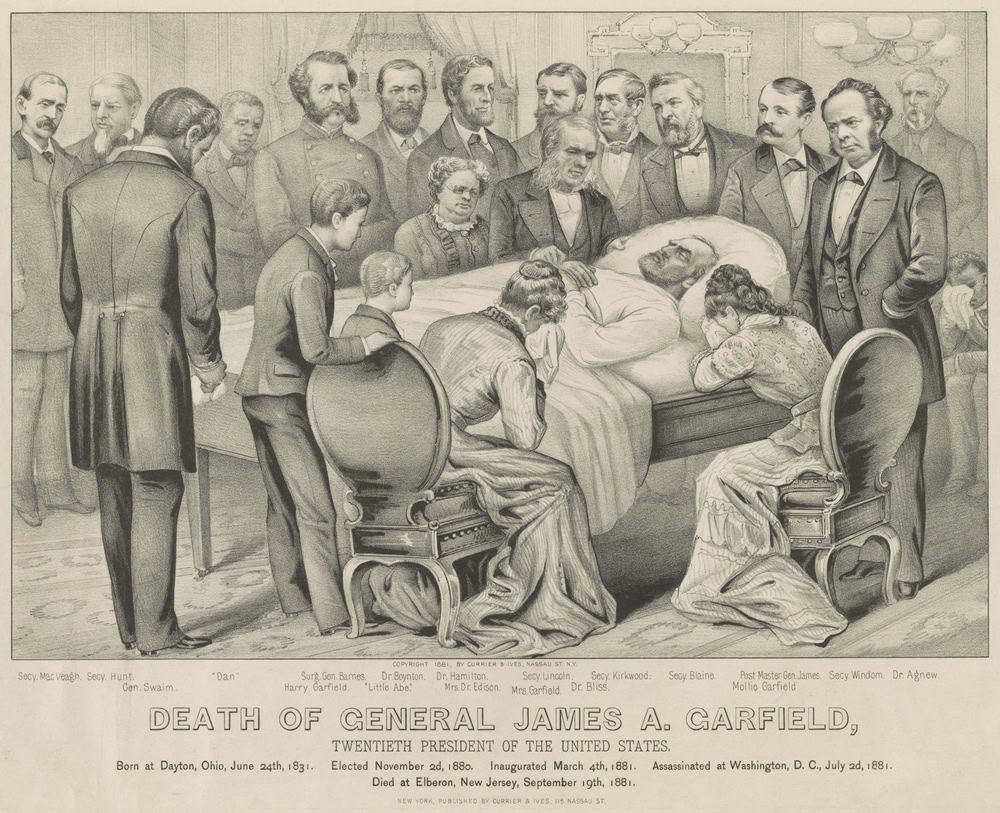

This was a time in history when germs were still misunderstood, Lister’s cleanliness practices were new and obscure, and the doctors, not knowing that the bullet that entered his back was lodged harmlessly beside his pancreas, stuck their unwashed fingers and various instruments into the wound, resulting in infection and sepsis. Garfield was taken back to The White House where he rallied briefly and continued for about two months to be subjected to the medieval medical practices of his doctors. In early September, the decision was taken to move the president to Long Branch on the Jersey shore, in the hope that the sea breezes would hasten his rehabilitation, but only 13 days later, on September 19th, President James Abram Garfield died after serving only 200 days.

Dancing, waving, smiling, and shaking hands on his walk to the gallows, Guiteau was hanged in June of 1882, astonished, to the end, that he was not celebrated for his act of murder, but certain that he was going to heaven; “I am going to the Lordy, I’m so glad,” were his last words. The pearl handled pistol he chose with a view to immortality was on display in the Smithsonian Institute in the early 20th century but has since been lost. His brain is still on display at the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia, revealing that he suffered from syphilis and chronic malaria, in conjunction with what is thought to have been madness caused by a fused foreskin.

In a five-page poem stating his case, Guiteau raved and rambled in an attempt to justify the assassination and invoked the fury of the Almighty Himself: “Some think me a devil. Some are lunatics. Some an inspired patriot. The last is right; And I stick to it! I Command, All men, everywhere, To believe it, Under penalty, Of God’s wrath. Charles Guiteau United States Jail Washington D.C [struck: M] June 1, 1882.”

Unfulfilled Promise

I think that, had he lived, Garfield would have been a spectacular president. He was a humanist, a realist, and an empath. “There is no horizontal stratification of society in this country like the rocks in the earth, that hold one class down below forevermore, and let another come to the surface to stay there forever. Our stratification is like the ocean, where every individual drop is free to move, and where from the sternest depths of the mighty deep any drop may come up to glitter on the highest wave that rolls.”1

A man shaped by his remarkable life experiences, learning, from the destitution and hardship of his childhood that poor people possess just as much possibility as the rich; through his co-ed college experience that women are men’s intellectual peers, from his time in New England that black people and white people are exactly the same, from his friendship with General Rosecranz that observing Catholicism and all religions besides his own does not qualify or disqualify a person from any opportunity they feel qualified to pursue from the loss of two of his own children that we all want the same things; all of these progressive positions were radical in the era in which Garfield lived. Sadly, many of our current leaders have not embraced these tenets. Tragically, Garfield was torn from a life spilling over with promise before he had a chance to implement any of his broadminded principles and plans. He died when he was only 50 years old.

- All quotes, except for the Charles Guiteau poem are taken from the letters, speeches and diaries of The James Abram Garfield Collection in The Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/collections/james-a-garfield-papers/.

You may want to read:

- Anne Boleyn: A Cautionary Tale For Modern Times?

- Hubris and Havoc: Wilhelm II and a Convicted President’s Parallels

- Putin & Napoleon: A True Story of Overreach, Hubris, and the Contemptible Betrayal of Paupers Passing Themselves off as Princes

- The Hand That Rocks The Cradle Rules The World

Join Us

Join us on this empowering journey as we explore, celebrate, and elevate “her story.” The Queen Zone is not just a platform; it’s a community where women from all walks of life can come together, share their experiences, and inspire one another. Welcome to a space where the female experience takes center stage. Sign up for our newsletter so you don’t miss a thing, Queen!